Replication refers to having copies of your data across different instances. It gives you redundancy when one of your instances goes down so you can still serve data to users from the remaining instances.

Another benefit of a replicated system is being able to load balance your requests across different instances. This can be useful when the load of serving all the requests from a single instance would be too much.

Finally, if you have users in different regions, replication gives you the option of deploying copies of your data closer to the users, reducing the latency of the requests.

In this post, I give an overview of how Postgres handles replication. One thing to note is that a lot of the strategies mentioned in this post are not only applicable to Postgres, but are common to many database systems.

Leader-Follower replication strategy

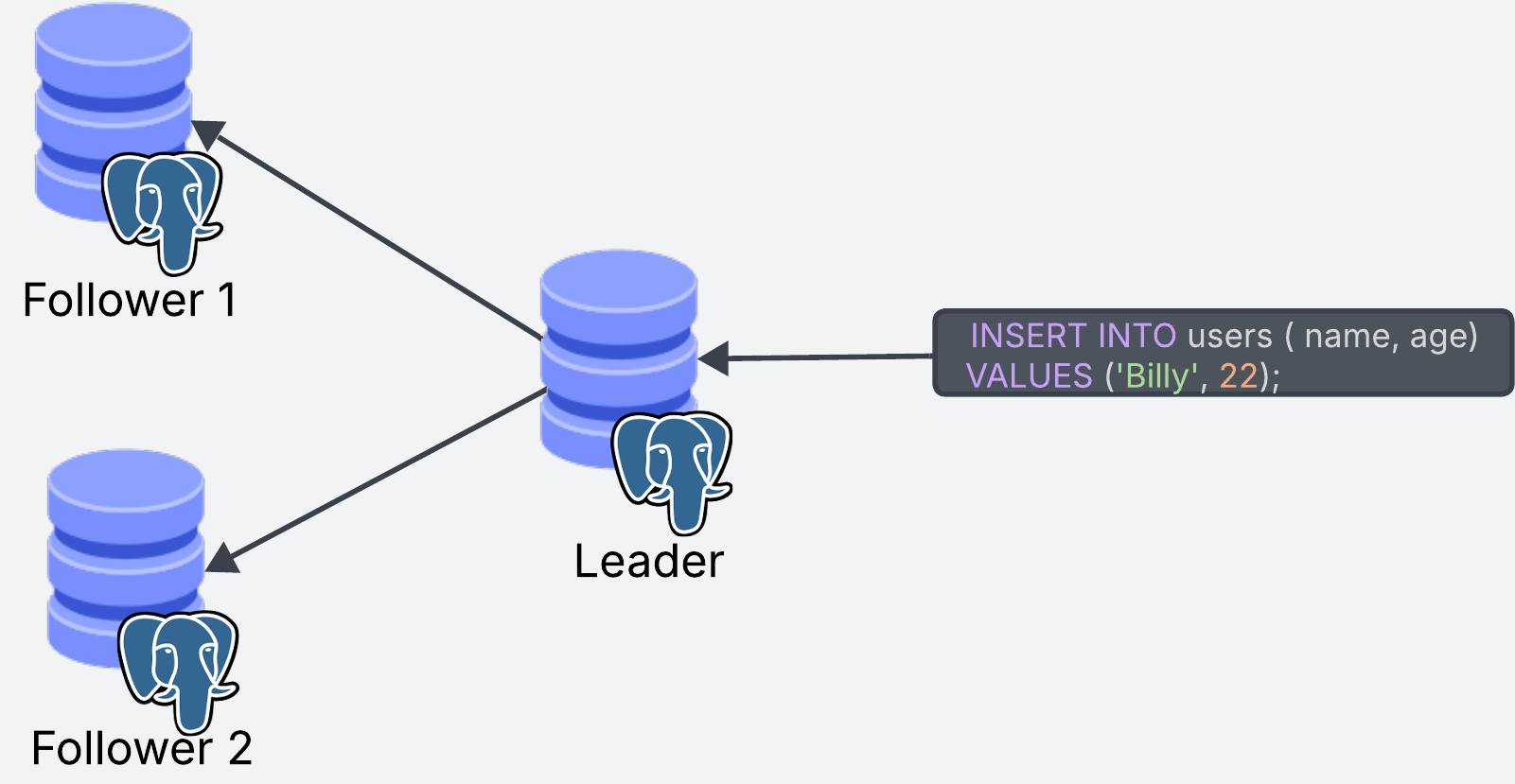

This is the most common strategy for replication across databases, and the one used by Postgres as well. In the Leader-Follower strategy, there are two types of replicas: leaders and followers.

The leader is in charge of the write operations to the database. Write operations can only go through the leader replica.

The follower replicas keep an up-to-date copy of the data from the leader. Whenever any data is written to the leader, the updates are propagated to the followers so they can stay up to date. Follower replicas can only do read operations (because read operations don’t change the data)

In Postgres, there is one leader but there can be more than one follower. When a write operation comes through, it goes to the leader, which then updates the follower replicas.

Read operations can go to any replica, including the leader.

Handling Failover

One of the main reasons for having replication is that if one of the replicas goes down, we are still able to serve data to our users through the other replicas. This is also known as high availability.

If you remember from the previous section, all the writes have to go through the leader, which creates a single point of failure for write operations. If the leader goes down, we won’t be able to serve write requests and users will only be able to run read operations from the follower replicas. This means write operations won’t be available until the leader comes back up, which could mean potential data loss if we are not able to process incoming requests.

A possible approach to handle such situations is to promote a follower to become the leader when the current leader fails. This is how systems like DynamoDB or Kafka handle these situations, but it is not part of Postgres by default.

There are third party tools that can be used to implement this functionality, but this adds a layer of complexity to the system. For example, if the leader fails and a follower becomes the new leader, and then the old leader comes back to life, we must have a mechanism for informing the old leader that it is no longer in charge. This is necessary to avoid situations where both systems think they are the leader, which will lead to confusion and ultimately data loss.

Sync vs Async replication

An important aspect of a replicated system is whether the replication process happens synchronously or asynchronously.

Synchronous Replication

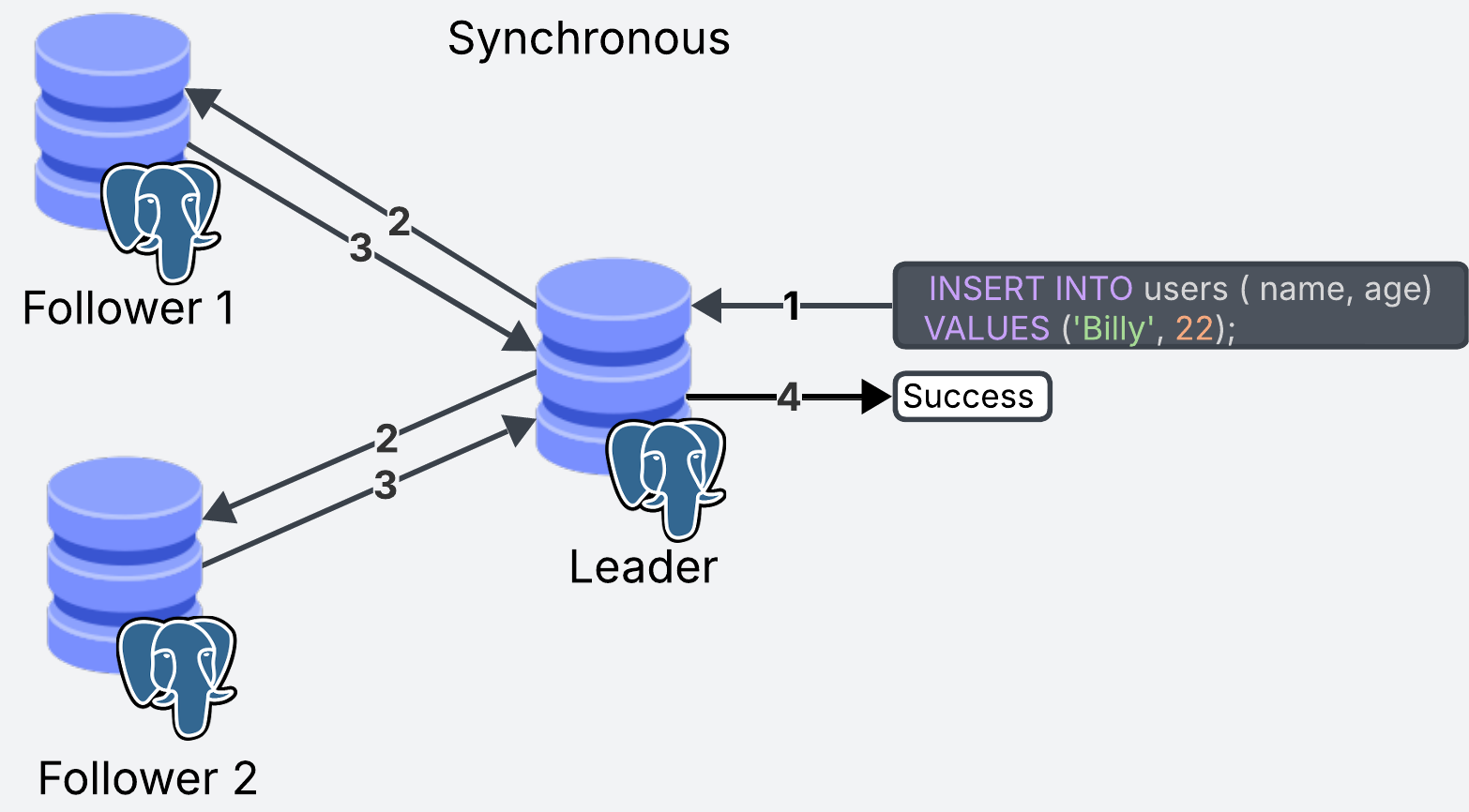

With synchronous replication, when the leader is updated, the transaction is not marked as complete until all the replicas have received the update.

The main advantage of synchronous replication is that all replicas will always be synced with up-to-date data. Multiple users, querying different replicas, will always get the same results.

The downside is that write operations will be slower since we need to wait until all replicas have been updated. Communication between replicas goes through the network, which means that if we have networking issues, the transaction can be slow.

From the diagram, keep in mind that steps 2 and 3 might take different amounts of time to execute on each replica. When working with a sync system, the transaction will be as slow as your slowest replica.

Slow writes will block further writes, which can cause issues if we deal with a high volume of transactions.

Asynchronous Replication

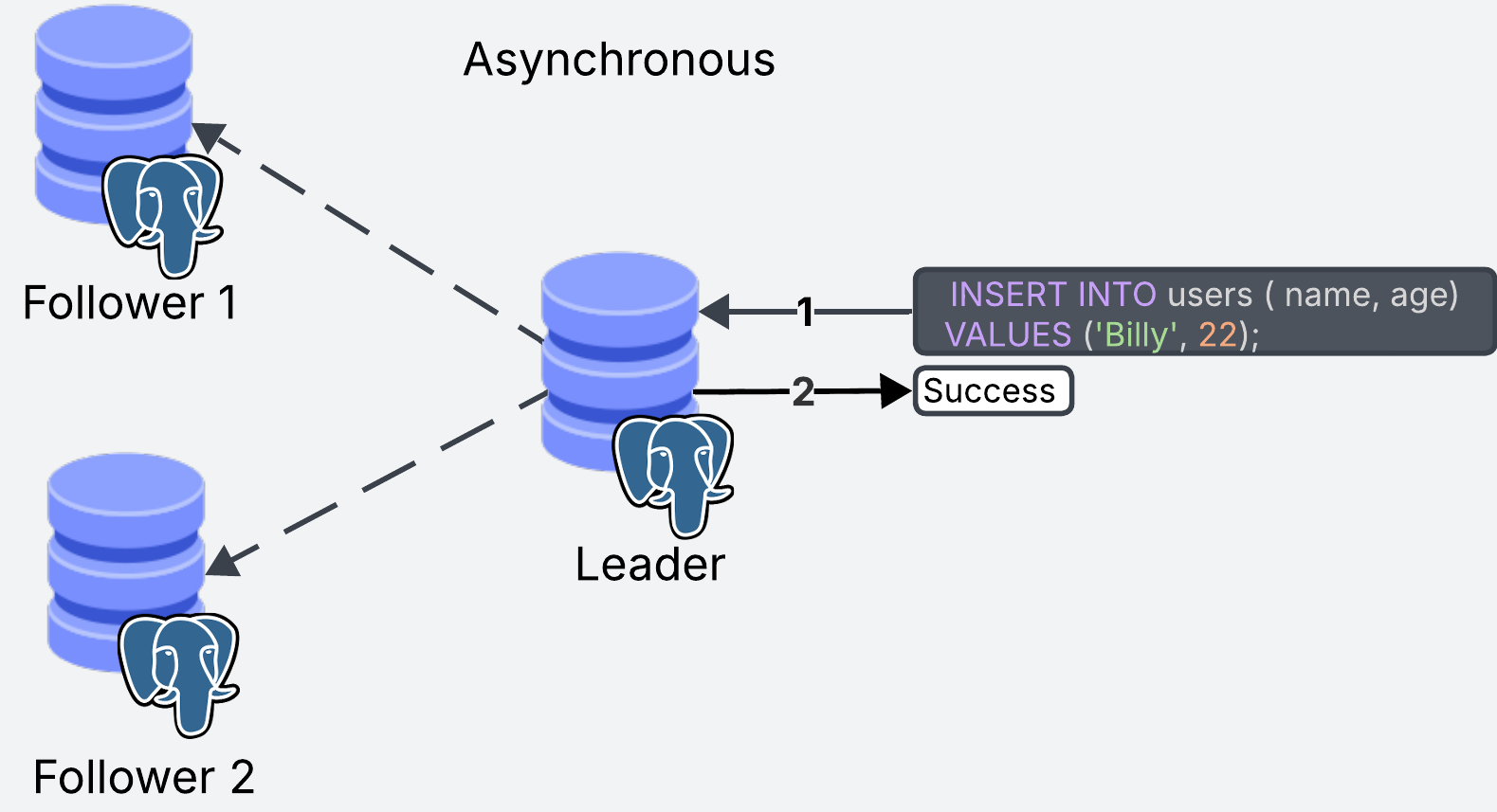

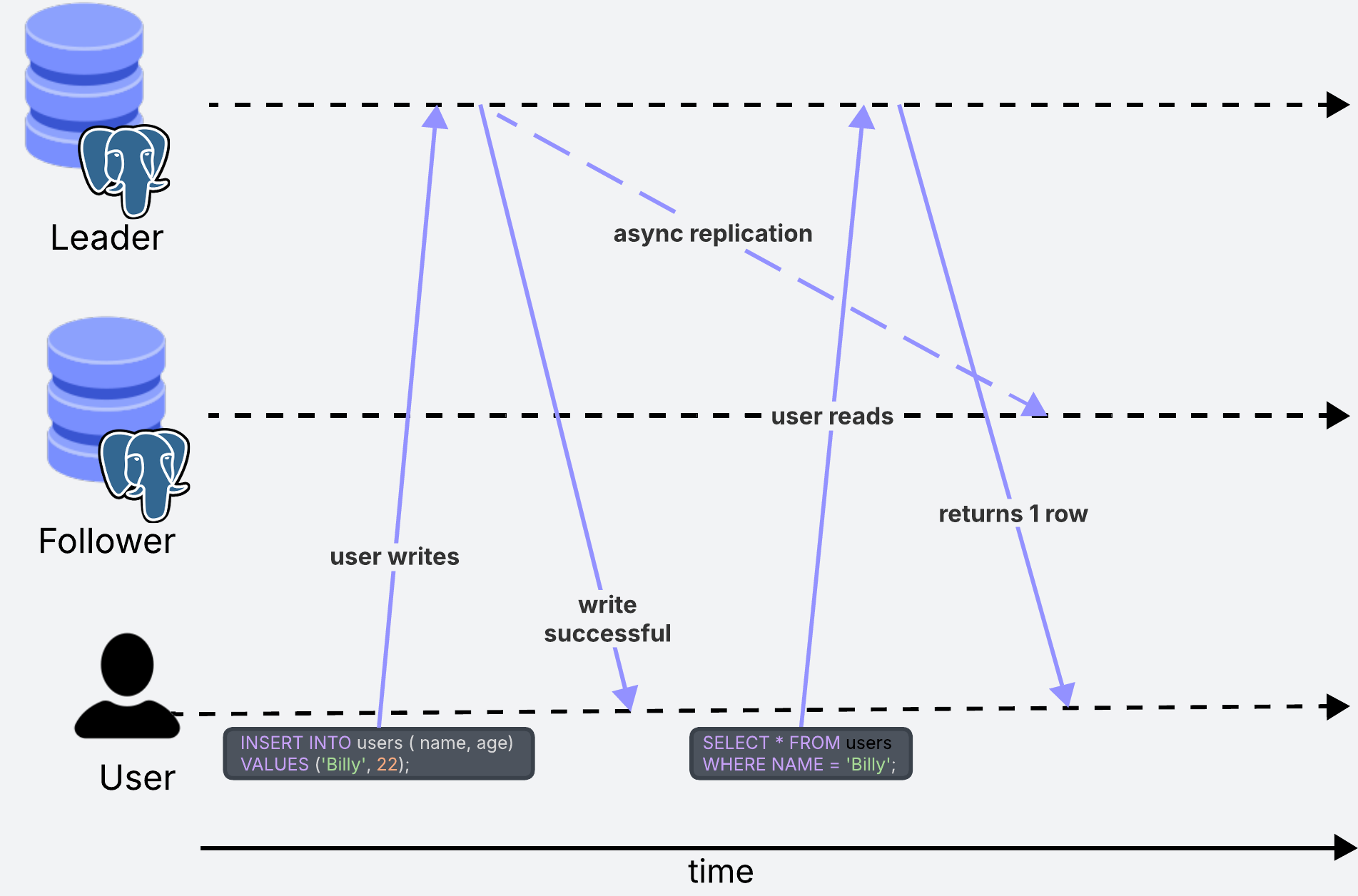

Asynchronous replication does not wait for the replicas to acknowledge the updates. As soon as the update happens in the leader replica, the transaction is marked as successful. The replicas are then updated asynchronously.

The main advantage of this approach is that the leader does not have to wait, meaning that writes are a lot faster. This is a common requirement for transactional systems with a high volume of writes.

The main downside is that users querying the same data, could potentially be getting outdated results.

Long story short, asynchronous replication is used when synchronous would be too slow. Postgres supports both types of replication strategies, using asynchronous by default.

Postgres also lets you have a mix of both approaches where the primary updates an n number of replicas synchronously, and uses asynchronous replication for the rest. This gives you the best of both worlds to keep some followers in sync with the primary without having to wait for every single follower to update.

Read After Write Consistency

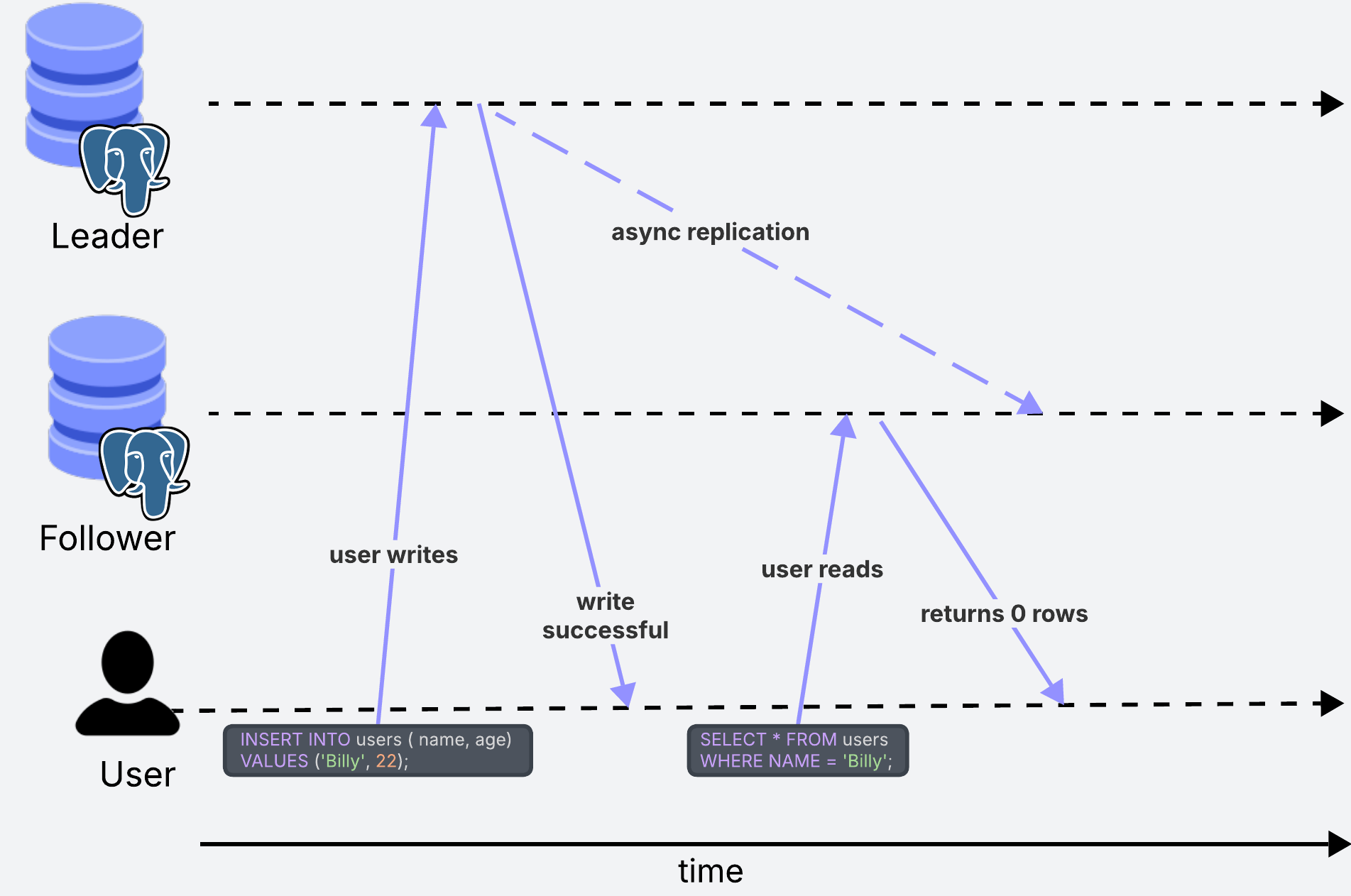

What happens in the scenario where one user writes some data, and then immediately after tries to read that data from a follower replica?

If we are using asynchronous replication, there could be a situation where the user reads data from the follower before it has had the chance to update. In this case, they would see outdated data. In some situations, this can lead to confusion.

For example, in a social media site, when a user updates their username it should immediately reflect that change to the user, otherwise they may think the change has not taken effect.

For example, in a social media site, when a user updates their username it should immediately reflect that change to the user, otherwise they may think the change has not taken effect.

This can happen when the update goes through the leader, but the user tries to read the changes immediately after from a follower replica which has not been updated. In this case, what we could do is to always read user profile information from the leader replica to ensure the user is always seeing the latest changes.

Reading from the leader can be a good solution for cases like this one, but if we find ourselves reading from the leader too much, we could end up putting too much strain on that instance, losing the benefit of load balancing read operations across the followers.

In other situations, users seeing outdated data might not be a problem at all. In the same example as before, this user’s friends will not care if for some time they see an outdated username of their friend.

Updating the replicas

So far, we’ve seen different strategies to work with a replicated Postgres database, but we still have no idea how the replication process happens.

When the leader receives a write operation, it gets logged into a log file. This file keeps an ordered history of all the write operations to the database. The logs act as a source of truth, so when the database crashes and restarts, it can compare its current state to what’s in the logs to get itself up to date.

In a replicated system, the log file is what actually gets sent to the follower replicas to get them up to date.

Write Ahead Logs (aka Write the Logs First)

But what happens if the database crashes mid-transaction before the log is written to the file?

When the database crashes, as it restarts, it will want to check the log file to find out what it is that it was meant to be doing before it crashed. If the log isn’t there, it does not know if whatever operation it was running had started, completed, partially completed or failed. In this case, the only safe option is to undo any changes in the database that are not recorded in the logs, leading to potential data loss.

The way to solve this problem is to write the log before the changes are written to the database. This is known as Write Ahead Logs (WAL). In this scenario, if the database crashes mid-operation, when it restarts, it can compare itself to the logs to know if the operation it was performing succeeded, partially succeeded or failed. Based on this information, it can take the corrective actions to get itself up to date.

There are different strategies on what to log in the file.

Logging the Statements

One approach is to log the actual SQL statements. The statements can then be run in order to recreate the data.

The main advantage is that the logs are very intuitive and easy to read. The problem is, when we have non-deterministic operations, we have no way of consistently replicating the outcomes each time the statement gets executed. This will be a problem when recovering after a crash or when replaying the transactions in the replicas.

Take this example:

-- Log 1

INSERT INTO users (id, name, age)

VALUES (1, 'Billy', 22);

-- Log 2

UPDATE users

SET id = FLOOR(RAND() * 100)

WHERE name = 'Billy';

-- Log 3

UPDATE accounts

SET balance = 150

WHERE id = 3;

-- Log 4

...

Log 2 won’t be replicable. Every time the statement gets executed, it will return a different result (unless you are very lucky).

Logging the Data Changes

To avoid such situations, Postgres actually logs the data changes rather than the SQL statements themselves.

For example, we run the SQL statement in memory first (without actually updating the data), we observe how the data will change, and we record it to the log. Using this method, we can replicate the data consistently even for non-deterministic operations because the statement is only run once. In this case, the log might look like this:

-- Log 1

Row inserted into "users": {id: 1, name: "Billy", age: 22}

-- Log 2

Row updated in "users" where name = "Billy": id changed from 1 to 57

-- Log 3

Row updated in "accounts" where id = 3: balance changed from 200 to 150

-- Log 4

...

In reality, these logs contain byte-level changes to disk rather than row level changes as shown in the example.

Thanks to the WAL, if any of the replicas goes down, as it restarts, it can look at the logs and replay all the changes from where it left off to become up to date with the leader.

Final Thoughts

Thanks for making it this far! Writing this has been an exercise for me to better understand replication in Postgres. During the writing of this post, I got to better understand the tradeoffs and limitations of Postgres as compared to other database systems.

It has sparked some questions, such as, why is more advanced failover not supported by default? It would increase availability in situations when the leader goes down.

The other question is, why is sharding not supported natively? This would add horizontal scalability to Postgres, rather than its current vertical scaling, which can be limited for larger scale applications.

I wonder if these are tradeoffs the developers have made the to reduce the moving components of running Postgres, making it easier to run and operate in production.

Resources:

- Designing data Intensive applications by Martin Kleppman (diagram ideas shamelessly stolen from the book)

- Postgres Documentation

Thanks to Gordon for providing feedback on an earlier version of this post.